Though it may seem otherwise, Ace Attorney Investigations: Miles Edgeworth (referred to as AAI from here on in) is not an easy game to pigeonhole. It could be considered as either a spinoff of the main Ace Attorney series or a full entry in its own right. It is the first and only Ace Attorney to feature both a prosecutor as the main character and a heavy emphasis on crime scene investigation. However, it’s as lengthy and as well written as many of its predecessors, and represents an evolution of, rather than a complete break from, the core Ace Attorney formula.

Spinoff or not, there’s no denying that this is a different sort of Ace Attorney. Set sometime after the events of the third game (Phoenix Wright Ace Attorney: Trials and Tribulations), it stars Miles Edgeworth, a savvy public prosecutor who’s both friend and foil to defense attorney Wright. It opens in Edgeworth’s office, where there’s been a murder, and the cases that follow only get bigger and messier from there. The goal of the game is to find the culprits for these cases by analyzing evidence and other information gathered throughout the course of the investigation. Typical for the series, AAI is funny and well-told, and while the plot can be predictable at times, in general, it is solid, anime-flavored drama. However, the localization suffers in spots from awkward grammar and typographical errors. It is far from the worst game localization I’ve ever seen, but it could’ve greatly benefited from an extra round of editing and polish.

Spinoff or not, there’s no denying that this is a different sort of Ace Attorney. Set sometime after the events of the third game (Phoenix Wright Ace Attorney: Trials and Tribulations), it stars Miles Edgeworth, a savvy public prosecutor who’s both friend and foil to defense attorney Wright. It opens in Edgeworth’s office, where there’s been a murder, and the cases that follow only get bigger and messier from there. The goal of the game is to find the culprits for these cases by analyzing evidence and other information gathered throughout the course of the investigation. Typical for the series, AAI is funny and well-told, and while the plot can be predictable at times, in general, it is solid, anime-flavored drama. However, the localization suffers in spots from awkward grammar and typographical errors. It is far from the worst game localization I’ve ever seen, but it could’ve greatly benefited from an extra round of editing and polish.

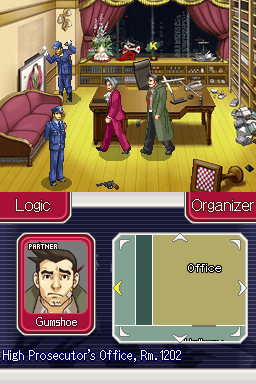

While convoluted murder cases are a hallmark of Ace Attorney, how they are handled is what truly sets AAI apart. Previous games took place entirely from a first-person point of view for the investigation phases, and only showed the main character during trials. In AAI, Edgeworth is represented onscreen nearly all the time. When he’s not in his typical 1/4 front portrait view, he’s a sprite on the top screen of the DS, and can be made to walk or run around his environment. This comes at the expense of the freedom to move between several different locations, as Ace Attorney‘s defense lawyers did, but is realistic within the context of the story, particularly when dealing with partner characters—no more running back to the office just to speak with your assistant! Other new features include the “Logic” command, where Edgeworth pieces together things he has noticed in order to explain something within the scene, and a device that recreates crime scenes, AAI‘s subtle, and suitable, upgrade from the previous games’ magical MacGuffins.

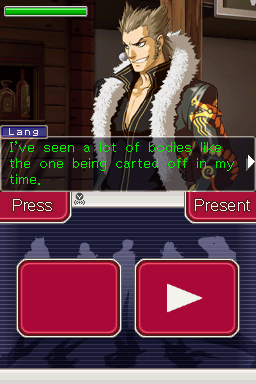

What else is different? The post-investigation phase in an Ace Attorney game typically involves a courtroom showdown, but not in AAI. Edgeworth still takes testimony and presses both witnesses and suspects, sure, but all of this action takes place right on the scene, and as such, is very tightly integrated with the investigation phases.

What else is different? The post-investigation phase in an Ace Attorney game typically involves a courtroom showdown, but not in AAI. Edgeworth still takes testimony and presses both witnesses and suspects, sure, but all of this action takes place right on the scene, and as such, is very tightly integrated with the investigation phases.

If all this sounds like a radical departure from the old formula, it’s one that fans need not worry about, as there’s much that hasn’t changed. The basic interface, for one, as well as the fact that the entire game (except for saving functions) can be played with just the touchscreen if one prefers. Speaking of controls, the ability to shout “Objection!” using the microphone has returned. Also handled in a familiar way are the first-person crime scene examinations, where a specific area can be searched for evidence; likewise, the basic process of interviewing witnesses and presenting evidence to them is the same as it’s always been. The visuals and music are stylistically consistent with the rest of the series, though the majority of the reused art assets—such as the portrait views for Edgeworth—have been given a much-needed facelift.

One “feature” that has been in the series all along—and is also present in AAI—is the methodical process that pervades throughout the cases, and the testimonies in particular. Often, it’s not all that difficult to figure out just what is going on at certain points in the story, but jumping too far ahead in one’s conclusions can have dire consequences, and the correct answers can be rather obtuse. Perhaps it is because I’ve played the previous games and am used to the Ace Attorney thinking process, but I encountered such stumbling blocks far less in AAI. That, along with the lack of real make-or-break, nail-biting moments, has made for what’s possibly the easiest Ace Attorney yet.

While we’re on the subject of familiarity: as mentioned before, there are many throwbacks to earlier titles in the series. From the appearance of beloved characters like police detective Dick Gumshoe, to tiny, Easter egg-like details, there’s much here that will put a smile on any Ace Attorney fan’s face. However, this has come at the expense of introducing more new characters to the canon; while there are some, the amount of them feels insufficient when compared to the earlier games. This heavy reliance on familiar elements, while not bad in and of itself, is the most spinoff-like aspect of AAI, and weakens its case for being a good starting point for newcomers.

So, is AAI just a spinoff, or a true Ace Attorney game? The verdict points to somewhere squarely in between. It’s a great adventure game, with a lot of excellent ideas that I’d like to see put to use in future Ace Attorneys, but it also relies heavily on the past, and has a localization that isn’t quite up to par with those of its predecessors. If you’re a fan, especially an Edgeworth fan, you’ll probably love it. AAI is a fan’s game, and while I don’t doubt that newcomers to Ace Attorney can and will enjoy it, one gets the sense that they’re not really who it was made for.

One of the original hybrid RPG stars has been, not unexpectedly, Mario. First in Super Mario RPG, then in the Paper Mario and Mario & Luigi games, the portly Italian plumber’s RPG adventures intermingle with the precise jumping and timing that define his platforming exploits. The Mario & Luigi series in particular adds an extra layer of challenge by having you control both Mario Bros. on the field at the same time, and eventually, special moves become available that can only be pulled off when the two are together. The second game, Partners in Time quadruples the party when Baby Mario and Baby Luigi join their older selves on the quest. This was also the first game in the series to appear on the Nintendo DS (the original was on the Game Boy Advance), occasionally reserving the top screen as the babies’ domain, with special areas only they can explore, for when they aren’t riding piggyback on the adults.

One of the original hybrid RPG stars has been, not unexpectedly, Mario. First in Super Mario RPG, then in the Paper Mario and Mario & Luigi games, the portly Italian plumber’s RPG adventures intermingle with the precise jumping and timing that define his platforming exploits. The Mario & Luigi series in particular adds an extra layer of challenge by having you control both Mario Bros. on the field at the same time, and eventually, special moves become available that can only be pulled off when the two are together. The second game, Partners in Time quadruples the party when Baby Mario and Baby Luigi join their older selves on the quest. This was also the first game in the series to appear on the Nintendo DS (the original was on the Game Boy Advance), occasionally reserving the top screen as the babies’ domain, with special areas only they can explore, for when they aren’t riding piggyback on the adults.