Last week over AIM, I said something to namatamiku that he didn’t expect to hear from me. In discussing my current addiction to Pokemon Ruby, I said that Pokemon “may just be the greatest game of all time,” later adding, “in all seriousness, I think the series as a whole is a strong contender for the title of Quintessential JRPG.”

A little bit of background first. Pokemon Ruby is the first game in the main series that I’ve ever played, though I’ve been familiar with the franchise since Red/Blue initially hit the States. Back then, I was in college and didn’t do much gaming myself. One of my classmates had gotten Pokemon Red and brought it into the studio one night. A handful of us watched her play, captivated by it. I’m not sure we knew why this was the case at the time, but clearly Nintendo was on to something, as Pokemon has since become one of the best-selling RPG series of all time. Since then, I played some rounds of Pokemon Stadium at another friend’s place, was exposed to the anime series (the only episode I clearly remember seeing all the way through was “Island of the Giant Pokemon”), and even acquired some jelly jars (though my Clefairy one broke, sadly). However, it wasn’t until last month that I started a main-series Pokemon game. It was between buying Pokemon Platinum, which had just come out, and borrowing my husband’s copy of Ruby; not sure if I would even like the series, and wanting to save some money, I went with the latter option. Now, here I am, over sixty hours in, with 80+ completed entries in my Pokedex and just one more gym badge to go, impressed by the game’s complexity and elegance.

A little bit of background first. Pokemon Ruby is the first game in the main series that I’ve ever played, though I’ve been familiar with the franchise since Red/Blue initially hit the States. Back then, I was in college and didn’t do much gaming myself. One of my classmates had gotten Pokemon Red and brought it into the studio one night. A handful of us watched her play, captivated by it. I’m not sure we knew why this was the case at the time, but clearly Nintendo was on to something, as Pokemon has since become one of the best-selling RPG series of all time. Since then, I played some rounds of Pokemon Stadium at another friend’s place, was exposed to the anime series (the only episode I clearly remember seeing all the way through was “Island of the Giant Pokemon”), and even acquired some jelly jars (though my Clefairy one broke, sadly). However, it wasn’t until last month that I started a main-series Pokemon game. It was between buying Pokemon Platinum, which had just come out, and borrowing my husband’s copy of Ruby; not sure if I would even like the series, and wanting to save some money, I went with the latter option. Now, here I am, over sixty hours in, with 80+ completed entries in my Pokedex and just one more gym badge to go, impressed by the game’s complexity and elegance.

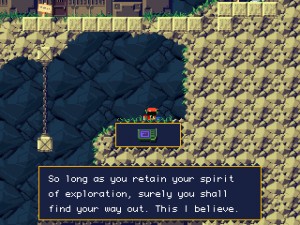

At its heart, Pokemon is a traditional turn-based RPG in the vein of Dragon Quest coupled with a simple plot pulled straight from the pages of Shonen Jump. Ruby starts you off in a small town in the Hoenn region, a world where everything revolves around Pokemon: work, play, shopping, travel, everything. You are a young novice trainer who sets off on a goal to become The Best. Along the way, there are wild Pokemon to capture, other trainers to challenge, and the overzealous Team Magma to deal with. All battle in the game is conducted by the Pokemon, up to six of which can be carried at a time, and just like playable characters in any other RPG, they can be level up, suffer from status effects, learn new abilities, and have their stats tweaked. There are two crucial differences however: Pokemon can only “know” four abilities total at any given time, and on top of that, many of them can also evolve into higher forms. Given that there are several dozen types of Pokemon in the game, each with their own strengths and weaknesses, and ranging in presentation from the cute to the badass, party management is perhaps the most important skill a Pokemon player must develop.

It is in this depth of variety, in the Pokemon species scattered across a handful of class-types, that the genius of Pokemon lies. Not only does the “gotta catch ’em all” aspect appeal to one’s inner collector, but just as the set limit on abilities forces hard decisions at times, so too does the collection itself. By making each Gym Leader—the game’s equivalent of bosses—a specialist in a certain type (or types) of Pokemon, balance in one’s party is (gradually) encouraged, and learning what’s super effective and what isn’t is often the most satisfying part of a successful match.

Which brings me to my next point: for a game series which is largely aimed at children, it is incredibly respectful of them. While there are hints and such given by NPCs throughout the game, there is no hand-holding, and challenging battles are handled the same straightforward way as easier ones. Additionally, the NPCs speak naturally, never talking down to the preteen protagonist (and by extension, the player), and fill a wide range of personalities, occupations, and ages. I believe that this honest, authentic approach is one major reason why the series is not only a big hit with children, but accessible to adults as well; Pokemon is best labeled an “all ages” series rather than a “kids” one.

I could go on. There’s the lively and exhilarating soundtrack; the Harvest Moon-esque berry cultivation; the subtle puns present in the names of several Pokemon species; the Pokemon Contests, clearly styled after dog shows and the like; the options available for Pokemon to learn abilities, evolve, and even level up outside of battle; and so on. Amazingly enough, somehow it all comes together in a tightly-packaged whole. I imagine that the multiplayer aspects of the series open it up even further, and from what I’ve seen in Ruby, this does appear to be the case. Still, it is one of those rare games with a heavy multiplayer bent where the single-player experience doesn’t suffer because of it.

From my experience thus far with Ruby, I feel that Pokemon is a game series that everyone should experience at least once. It takes the best aspects of Japanese RPGs and pulls them all together in a unique, engrossing way. Sure, it has a reputation for sameness between installments, but for most people one title should be plenty, and if there’s ever an urge to pick up another, then I see no harm in that. After all, this is what my husband did not long after I started Ruby; getting nostalgic for the game, and unable to create a second save file on the cart, he went out and got Platinum instead. His Pokedex numbers and Gym Badge collection still have to catch up with mine, though!

A little bit of background first. Pokemon Ruby is the first game in the main series that I’ve ever played, though I’ve been familiar with the franchise since Red/Blue initially hit the States. Back then, I was in college and didn’t do much gaming myself. One of my classmates had gotten Pokemon Red and brought it into the studio one night. A handful of us watched her play, captivated by it. I’m not sure we knew why this was the case at the time, but clearly Nintendo was on to something, as Pokemon has since become one of the best-selling RPG series of all time. Since then, I played some rounds of Pokemon Stadium at another friend’s place, was exposed to the anime series (the only episode I clearly remember seeing all the way through was “Island of the Giant Pokemon”), and even acquired some jelly jars (though my Clefairy one broke, sadly). However, it wasn’t until last month that I started a main-series Pokemon game. It was between buying Pokemon Platinum, which had just come out, and borrowing my husband’s copy of Ruby; not sure if I would even like the series, and wanting to save some money, I went with the latter option. Now, here I am, over sixty hours in, with 80+ completed entries in my Pokedex and just one more gym badge to go, impressed by the game’s complexity and elegance.

A little bit of background first. Pokemon Ruby is the first game in the main series that I’ve ever played, though I’ve been familiar with the franchise since Red/Blue initially hit the States. Back then, I was in college and didn’t do much gaming myself. One of my classmates had gotten Pokemon Red and brought it into the studio one night. A handful of us watched her play, captivated by it. I’m not sure we knew why this was the case at the time, but clearly Nintendo was on to something, as Pokemon has since become one of the best-selling RPG series of all time. Since then, I played some rounds of Pokemon Stadium at another friend’s place, was exposed to the anime series (the only episode I clearly remember seeing all the way through was “Island of the Giant Pokemon”), and even acquired some jelly jars (though my Clefairy one broke, sadly). However, it wasn’t until last month that I started a main-series Pokemon game. It was between buying Pokemon Platinum, which had just come out, and borrowing my husband’s copy of Ruby; not sure if I would even like the series, and wanting to save some money, I went with the latter option. Now, here I am, over sixty hours in, with 80+ completed entries in my Pokedex and just one more gym badge to go, impressed by the game’s complexity and elegance.