For the past few years, I’ve been tying up some final loose ends in the old school JRPG space. I never set out to play everything—for instance, I’ve no plans on touching Xenogears, for an assortment of reasons—but there have been a handful of titles that I’ve slowly been getting around to. Last year’s non-port, non-remake relics were Earthbound and Secret of Mana; I didn’t like them, but couldn’t hate them, either. The former was archaic (even for the time) and sported certain horrible and frustrating bits of game design, but its charming atmosphere made it easy to see why it has garnered a fervent fanbase to this day. The latter has a clunky interface and AI, overenthusiastic animation, and a rushed translation, yet the rest holds up fairly well, and in general, the game wears its ambition proudly.

This year’s major relic is Chrono Cross, the PS1 sequel to a Super Nintendo game made by a once-in-a-lifetime “Dream Team”; a console RPG which has since become one of the most beloved of all time. With such a pedigree, Chrono Cross has a lot riding on it. On top of that, aside from executive producer Hironobu Sakaguchi and composer Yasunori Mitsuda, none of the most recognizable names from the aforementioned original game’s “Dream Team” show up here. This doesn’t bode well, but it’s unrealistic to believe that Chrono Cross would equal or even surpass its legendary predecessor, right? As long as it works, there shouldn’t be much to worry about, right?

Well, therein lies the rub. Chrono Cross doesn’t work, not as a whole. Rather, it should, it ought to, parts of it do sometimes, and it contains so many things that could make everything work, but they all fit together in the wrong way, or too much glue is used in one place, and not in another. The result is a goopy mess of wasted potential, a skunk works project that looks good on the surface, but creaks at the seams.

This is a JRPG where the protagonist adventures with only the barest of motivations even after a few hours in, and with little to no pressure from outside forces pushing him forward; sometimes, when said pressure does come to bear on him, events then progress in a such a way that make absolutely no sense in the context of what happened even just a scene or two before. This is a tale where, whenever the central plot rears its ugly head, it starts out presenting itself in a natural and fluid way, then bombards you, via whatever deux ex machina device happens to be available, with tons of information that confuses things once again before, during, and/or after a major boss fight. This is a plot in which, toward the end, when things do kind-of sort-of make sense now, the last little bits thrown at you are absolutely ludicrous and makes you wonder what kind of crack the writers were smoking.

This is a game that commits one of the gravest crimes of game design: instead of guiding the player whenever necessary, it makes assumptions of them. It assumes that the player will go in a certain direction once heading to a new town with an open main square that happens to have several branching paths, so that the entire place can be explored before triggering the very cutscene that hints as to you why the townsfolk were talking about the things they were. That’s not a problem, but what is is that it also assumes that the player will remember every single snippet of conversation, amongst many dozens of characters and across several locations, that takes place throughout the course of the game. As such, this is a game in which a strategy guide or online walkthrough won’t be wanted merely for the optional stuff (and there’s a ton), but just for figuring out how to progress through the damned story. I don’t know how much is the fault of the localization—the PlayStation era was hardly a golden age for English translations of Squaresoft games—or the writing itself, but either way, a game like this should not have a narrative structure this sloppy.

Then there’s the battle system, which confuses simplicity with elegance, and complexity with depth. This may sound strange considering the genre, but in the Chrono Cross system, there are just too many numbers. Don’t get me wrong; it’s not the numbers themselves, but the types of numbers. There are percentages and decimals all over your average battle screen, along with blinking graphs for your Elements (Chrono Cross‘ version of spells and healing items) and your usual HP indicators. It’s a system that closely integrates turns with three different grades of physical attack, the aforementioned Elements, field effects, and summons that are both rare and borderline useless. Leveling has been completely done away with, but party members can still earn stat upgrades at the end of each battle, which kind of makes one wonder what the point of having no levels is. It’s a highly unusual and experimental battle system—par for the course for a ’90s Square JRPG, when you think about it—but suffers from the same syndrome that Kingdom Hearts II did in that the regular enemies tend to be too easy, while certain boss fights ramp up the difficulty a noticeable amount. Even with the latter taken into account, it’s possible to run away from several boss battles, including the very last one, so perhaps I’m overstating the difficulty there.

And speaking of the final boss, there are two options to dealing with it, and one of them requires an item that is talked about many times, but can only be obtained by going someplace that isn’t labeled on the map and is referred to but once or twice (without any clear indicators that You Should Go There) during the regular course of the game. Using this item, well, that’s another matter entirely. Let me save you the trouble: unless you really, really like exploring, don’t bother searching for hints in the game—if you want the “good” ending, skim through an FAQ to get the details.

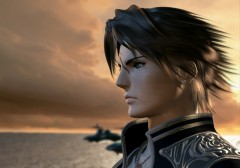

However, before you think that this review is all negative, rest assured that there were some things I liked about Chrono Cross. While I found main character Serge to be bland—even for a cipher—and heroine Kid a bit annoying, there were some cast members I genuinely liked, such as Norris. Certain references to the game’s predecessor that popped up early on were kind of cute. For the most part, and despite the ugliness of PlayStation graphics in general, the visual aesthetic was nice. One of the main subplots was largely enjoyable and quite touching, although a certain track associated with it wore out its welcome really fast. And speaking of music, Yasunori Mitsuda’s score was great; I went in thinking that I wouldn’t like it, as I’d been overexposed to a handful of pieces over the years, but the soundtrack as a whole grew on me.

So, in summation, don’t play Chrono Cross, especially if you’re, like me, someone who loved its predecessor to bits and would be put off by an inferior battle system and convoluted, inelegant lump of a story. Just go straight to your favorite Japanese import game music retailer and plunk down ¥3,204 or thereabouts for the soundtrack instead. That way, you’ll get one of the very best parts of the game without actually having to play it!